I’m going to wager that there aren’t many of you out there wondering about the implications of a player transaction from 122 years ago.

I’ll double-down and say that some of you only have a passing knowledge of who Christy Mathewson is, or was (see: dead since 1925), and you certainly aren’t maintaining an active membership in the Amos Rusie Fan Club, though maybe you should.

But I will say this: if you’re a baseball fan, and why would you be here otherwise, the story behind these two Hall of Famers, and the trade that binds them together, will make you a fan of both them and their intertwining stories.

The fact that two Hall of Fame pitchers on the extreme opposite sides of their careers is a good place to start, but add in interclub collusion to save $900 amidst a failed coup, a revenge plot, some light collusion turning heavy, and negotiations by one club to sell itself… to the other owner (are you lost yet?) and you’ve got yourself a truly bizarre and notable transaction.

“YOU CAN’T HIT ‘EM IF YOU CAN’T SEE ‘EM”

Amos Rusie’s claim to fame was both as a revolutionary of velocity in the game in the 1890s, as well as one of the most feared and erratic hurlers of his time because of his historic propensity to issue walks, wild pitches and hit batters.

Put simply, homeboy had almost no idea where the ball was going once it was released from his hand.

Debuting for a relief appearance on May 9, 1889 with the Indianapolis Hoosiers, the 17-year-old Rusie made his first career start in a 16-11 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates at Seventh Street Park III on June 15, 1889 and finished his rookie season with a 12-10 record, a pretty-good-for-his-age 5.32 ERA and an 0.94 K/BB (109/116) ratio that is as unseemly as it gets, yet would become a staple of Rusie’s short, but spectacular career.

Rusie also had a teammate on that ’89 Hoosiers club named Pretzels Getzien, which has nothing to do with nothing, but what a name!

I will absolutely write about Getzien and the origin of that name when time permits.

After the Hoosiers folded at the conclusion of the 1889 season, Rusie and his teammates were dispersed throughout the league, with Rusie off to the New York Giants.

(Pretzels went to Brooklyn).

Rusie’s first season in New York was a statistical mixed bag, with his 289 walks in 1890 remaining tops in The Show to this day, unlikely to ever be approached, matched or topped, unless of course Tony La Russa is given another managerial job to sleep through.

But just as his walks were eye-catching, so, too, were his 29 wins (!) and 34 losses(!!!), along with 56 complete games in 62 starts.

But his 341 strikeouts usurped all of that in the minds of observers back then, not just because of the quantity, but the velocity with which he collected them.

Rusie pitched well before radar guns existed, so the barometer used to measure the speed of his fastball was essentially the eye test, and to the eyes of everyone observing him, opposing batters, teammates and onlookers alike, Rusie was second to none, rumored to throw somewhere in the upper 90s, which would have been downright bewildering in the late 19th century/early to mid 20th century.

Rusie’s contemporary, the legendary John McGraw, once opined about facing Rusie’s fastball, “you can’t hit ’em if you can’t see ’em.”

Yeah, tell that to Aroldis Chapman.

A native of Mooresville, Indiana, Rusie became a celebrity in New York during that first season with the Giants, living large in the Big Apple, enjoying beverages named in his honor, taking in vaudeville skits portraying his growing legend, and seemed to live in the moment, never taking life too seriously and being looked upon as generally pleasant and joyously aloof.

Ever the carouser in his day, Rusie never allowed his off-field activities interfere with his on-field performance, though the many batters ducking his fastballs as they sped past their heads for the third time that particular day would probably beg to differ.

By the time Rusie turned 21, he had already eclipsed over 1,200 innings at the big league level, a staggering amount of usage for someone revolutionizing the dual role of the game’s first proper power pitcher as well as the king of the base on balls.

Rusie would never match his 1890 strikeout total, but he continued to lead the league in the category overfour of the next five seasons that followed.

In 1893, with league-wide batting averages in sharp decline, primarily due to Rusie and others (somewhat) like him who pitched with more power and velocity, MLB decided to move the mound back from 55 feet, 6 inches to 60 feet, 6 inches – where it has remained to this day.

MLB achieved its desired sharp increase in offense, and Rusie, unlike many contemporaries, didn’t miss a beat.

In 1894, Rusie authored his masterpiece, winning the pitching Triple Crown, leading the league in all three categories with 36 wins, 195 strikeouts, and a 2.78 ERA as the Giants rode Rusie to a Temple Cup Championship (prehistoric World Series, but also kind of not).

Rusie’s career would continue to impress, but was marred by a dispute with Giants owner Andrew Freedman in 1895 over $200 in fines levied for such vague acts as curfew violation and “not trying hard enough.”

Rusie’s salary that year was $3,000, so the withholding of $200 at the end of the season was no small matter and sent the Giants star into a rage.

Rusie sued the Giants for $5,000 and for release from his Giants contract, opting to sit out the entire 1896 season while his case was worked through the courts.

Fearing an end to the Reserve Clause that kept players in servitude to the whims and whimsies of their controlling franchises, National League owners pushed Freedman, a former politician only two years into his ownership and already the most reviled owner in baseball, to settle.

When Freedman refused, the rest of the league’s owners conceded on his behalf without his knowledge or approval, surrendering $5,000 to Rusie and welcoming him back to the Giants for the 1897 season.

A little later, you’re going to learn that Andrew Freedman takes his grudges seriously.

After a solid 1897 season that saw Rusie issue a career-low 87 walks in a wonderful comeback campaign that rivaled his high-watermark season of 1894, Rusie entered the 1898 season at 27 years-old, brimming with confidence and hope that the Giants would build upon their 83-win, third-place finish.

In an August contest against the Chicago Orphans (prehistoric Cubs), with Orphans outfielder and 1897 NL stolen base leader Bill Lange on first, Rusie attempted to snap a throw to first without taking a step towards first or moving his feet in any way.

As the ball left Rusie’s hand, his shoulder snapped.

Rusie’s attempt to pick Lange off was successful, but the pain in his arm spread and his ability to throw his patented fastball was gone.

“My arm felt dead,” Rusie told the Sporting News decades later in December 1939. “I finished the game throwing floating curves.”

Rusie took five weeks off at the behest of a team of doctors acting on rudimentary, often conflicting diagnoses.

“When I returned to the firing line, my arm felt okay,” Rusie said in the same Sporting News piece. “The zip in my fast one was still there; my curve crackled and snapped. For the rest of the season, everything was fine. But the following spring, when I tried to pitch, my arm felt dead. I took my turn on the hill, but every effort was followed by nights of torture, during which I walked the floor. So I had to hang up my glove.”

Rusie, still property of the Giants, rested his arm for two years, staying far from the game.

As the 20th century began, the Giants were in the cellar of the National League, finishing 60-78, and, as you’ll learn, weren’t terribly pissed at that fact. But try as they might, the Giants could not keep from planting the seeds of a historically successive winner, starting with a semi-pro purchase.

THE ORIGINAL MATTY ICE

In July of 1900, the Giants took a flyer on a 19-year-old right-hander from Norfolk of the Virginia League by the name of Christopher “Christy” Mathewson.

Mathewson, a football star at Bucknell University, as well as an above-average baseball and basketball player, had already pitched professionally in the ill-fated New England League at 17 years-old, going a dismal 2-13 for Taunton, Massachusetts before the league folded mid-season.

In 1900, Mathewson once again tried his hand at pro ball, signing with Norfolk and, by July, was 20-2 and becoming an asset that Norfolk owner Phenomenal Smith (an admittedly odd name for a guy who finished his MLB career 20 games under .500) knew he needed to cash in on.

Smith gave Mathewson two choices – New York or the Philadelphia Phillies.

Believing that the Giants were more pitching-hungry and able to provide him an opportunity to pitch, Mathewson chose New York.

It didn’t go well.

Mathewson pitched in six games that season, surrendering 32 runs (19 earned) in 33.2 innings with a dismal 0.75 K/BB rate and a disastrous 4.46 FIP.

Just writing those stats in 1900 would probably have blown peoples’ minds. I’d have liked to have seen Grantland Rice try and calculate FIP.

The Giants, unimpressed with Mathewson’s showing in a fairly small sample size for a teenager, sold him back to Norfolk in December 1900, with Mathewson himself fine to leave New York, writing to a friend at the time that he “didn’t give a rap whether (the Giants) sign me or not.”

Before the calendar flipped to 1901, the Giants and Cincinnati Reds would engage in an act of blatant collusion; a small part of a larger plot by Freedman to obtain revenge upon a league that had enraged him.

AN ACT OF ANTI-SEMOTISM AND A REVERSED SUSPENSION

During an 1898 match-up between the Giants and Baltimore Orioles at the Polo Grounds, former Giants outfielder Ducky Holmes, who had been traded the previous season by New York to the St. Louis Browns, struck out in the fourth inning.

As Holmes made his way back to the dugout amidst jeers from the Giants faithful, he directed anti-Semitic slurs directly at his former employer, Giants owner Andrew Freedman, himself a man of German-Jewish heritage.

Enraged, Freedman demanded that Holmes be thrown from the game and the grounds. After umpire Tom Lynch refused to cede to his demands, Freedman pulled his Giants from the field and Lynch forfeited the game for the Orioles.

The league, however, would issue a season-long suspension for Holmes.

Immediately after, America’s larger indifference to racism showed up, with Boston players (yeah, a completely uninvolved club) circulated a petition for anyone in the game to sign, denouncing Freedman’s “spirit of intolerance, of arrogance and prejudice toward players, a spirit inimical to the best interests of the game,” while publications throughout the country played down the trifling act of a little bit of fun racism.

Some late 19th century locker room talk, if you will.

A local Baltimore judge intervened and gave Holmes injunctive relief after just a few days on the sidelines, ending the suspension.

What really pissed Freedman off though was that his fellow owners, who had stepped in to end Rusie’s holdout just a year prior, had actually sided with Holmes based on the fact that the suspension was issued without a hearing (and probably more likely because their love of procedural integrity was only rivaled by their love of protecting what they probably construed as constitutional racism).

From that point on, Freedman, a mercurial and heavily-disdained man in his own right, was resolved to punish baseball by purposely sinking his own franchise to hurt baseball’s larger financial picture.

Freedman, because of his immense personal wealth, viewed ownership of a baseball team as no more than a hobby – one that he could easily absorb losses for if it meant hurting the league he no longer cared to help or partake in productively.

The Giants’ fortunes sunk in 1899, with the team dropping to the bottom of the league and attendance sinking just as fast.

The Giants, baseball’s crown jewel financially before the rift, had dealt MLB a crippling financial blow.

In an interview with Sporting Life in September of 1899, dropped this incredible quote, telling the world that “base ball affairs in New York have been going just as I wished and expected them to go. I have given the club little attention and I would not give five cents for the best base ball player in the world to strengthen it.”

Damn.

If anyone ever wonders why I could care less about steroids or sign-stealing or juiced balls, it’s because owners have been doing this shit since the jump and the only difference between 2022 and 1899 is that back at the end of the 19th century, an owner like Freedman said the quiet part out loud, confident that there was no consequence to follow those words.

It’s safe to say then that the July purchase of Mathewson was, more or less, just a way to fill the roster on the cheap with no eye for his potential (and eventual) greatness.

By December, Mathewson was awaiting his fate and the Giants were hatching a plan to save some money while jettisoning a star for what Freedman assumed would be nothing.

As part of their purchase agreement of Mathewson’s rights from Norfolk, the Giants agreed to pay Norfolk $1,000 if Mathewson was part of the team by the end of the year (not the season, the year – a shady stipulation that those running the Norfolk club clearly didn’t see).

So, in December, the Giants returned Mathewson to Norfolk.

A few, short days later, the Reds selected Mathewson in the Rule 5 Draft for only $100.

On December 15, the Reds traded Mathewson to the Giants for Amos Rusie, who hadn’t thrown a pitch in two years.

Norfolk was out $900, the Reds assumed damaged goods in Rusie, and the Giants got Mathewson, who would almost instantly become one of the greatest and most dominant pitchers even to this day, for nothing at all.

The alliance between Freedman and Reds owner John T. Brush was more than just a passing transaction.

It was a footnote in a partnership that was giving birth to a larger syndicate scheme by Brush to convert independently-owned National League clubs into a jointly held trust.

Within the Trust, players and coaches would be “licensed by the board and assigned to various teams consistent with establishing competitive parity. Costs would be controlled by means of stringent salary caps and by the manufacture of baseball equipment by a Trust subsidiary. Apportioned profits to Trust shareholders would be meted out at season’s end.”

The Trust (narrowly) failed to pass a vote at the National League meetings in December 1901 and Freedman suffered a PR nightmare as a result of his heavy involvement in fighting for passage against anti-Trust champion A.G. Spalding.

After the Trust collapsed, Freedman would participate in more sideways schemes, joining Brush in convincing John McGraw, the mercurial player/manager/part-owner of the revived Baltimore Orioles to release his interests in the team to Brush, who ceded them… to Freedman, who immediately released all of Baltimore’s best players (RHP Joe McGinnity, 1B Dan McGann, OF Roger Bresnahan, RHP Jack Cronin) who all signed with his other team, the Giants… or the Reds (OFs Joe Kelley and Cy Seymour).

Oh, and McGraw? He became the newest manager of the New York Giants.

American League President Ban Johnson immediately stripped Freedman of control of the team and placed it under control of the league for the remainder of the season before they relocated the franchise to New York and it started anew as the Yankees.

In 1902, after an eventful four years to say the least, Freedman ceded control of the Giants… to John T. Brush.

In four years, Freedman, fueled by anger, hatred, and fortuitous wealth, had sunk baseball’s most profitable franchise on purpose, decimating baseball’s finances with all the thoughtfulness of someone who tosses a penny in a mall fountain, then (narrowly) failed to install a faceless Trust system that would have adhered players to even more financial indignity than the Reserve Clause could muster.

The grand finale was taking ownership of a second team and then immediately draining it of all of its assets to help his other team, knowing full-well that it would cost him ownership of said second team and knowing the whole time that he owned nary a fuck to give about it.

But lost in all of that was a tiny transaction that sent the legendary Rusie to the Reds in exchange for a kid that they didn’t want to pay a dime for.

Under the Brush/McGraw regime, the Giants immediately returned to prominence, with the stolen McGinnity (31-20) and Mathewson (30-13) anchoring a rotation that helped lead the Giants to an unparalleled stretch of success, with only three losing seasons between 1903 and 1939, four World Series titles (1905, 1921, 1922, and 1933), and with McGraw leading the team through the midpoint of the 1932 season.

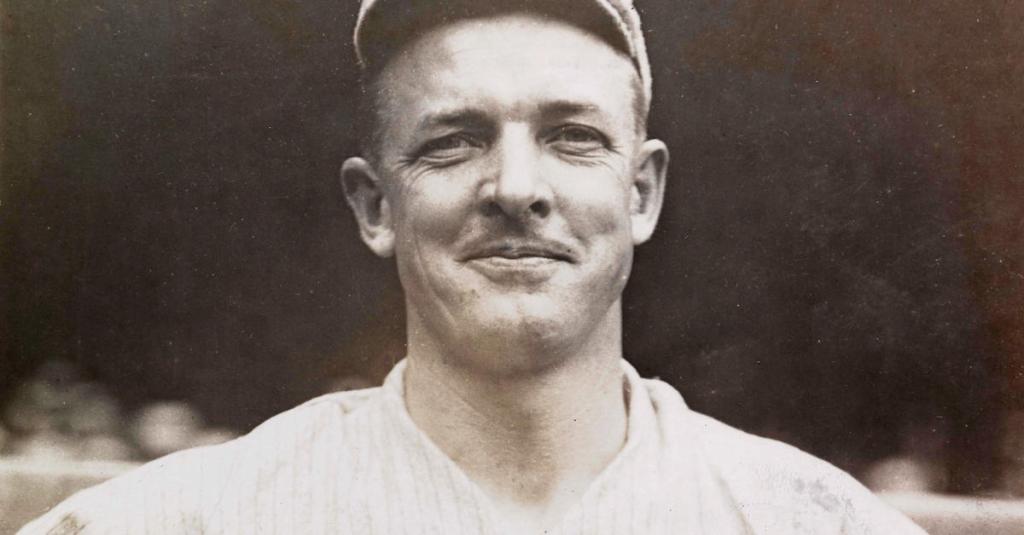

Mathewson, or “Matty”, would win 373 games (t-3rd all-time) in 17 years with a mind-blowing 2.13 ERA (8th all-time), a 136 ERA+ (t-25th all-time), 100.4 wins above replacement (10th all-time), and the title of Greatest Pitcher of the Decade from 1900-1912, usurping the very man he replaced in New York.

Rusie, fresh off of two years of rest, negotiated a $1,500 salary with the Reds ahead of the 1901 season and would go 0-1 in three lousy games; his final being a start in Cincinnati on June 9, 1901 against the Giants, a game that would see 17,000 spectators surround the diamond, pushing ever-so-close to where outfielders were stationed.

The game ended in a forfeit brought on by fans rushing the field in the ninth inning with the Giants leading, 25-13.

The Giants received the win and Rusie never played again, quietly hanging up his glove and heading home to Indiana.

Matty, dogged by a pain on his left side since the 1914 season, would see his effectiveness diminish over the next two seasons, compelling his request midway through the 1916 season to be traded to – you won’t believe it – the Cincinnati Reds, where he would serve as manager.

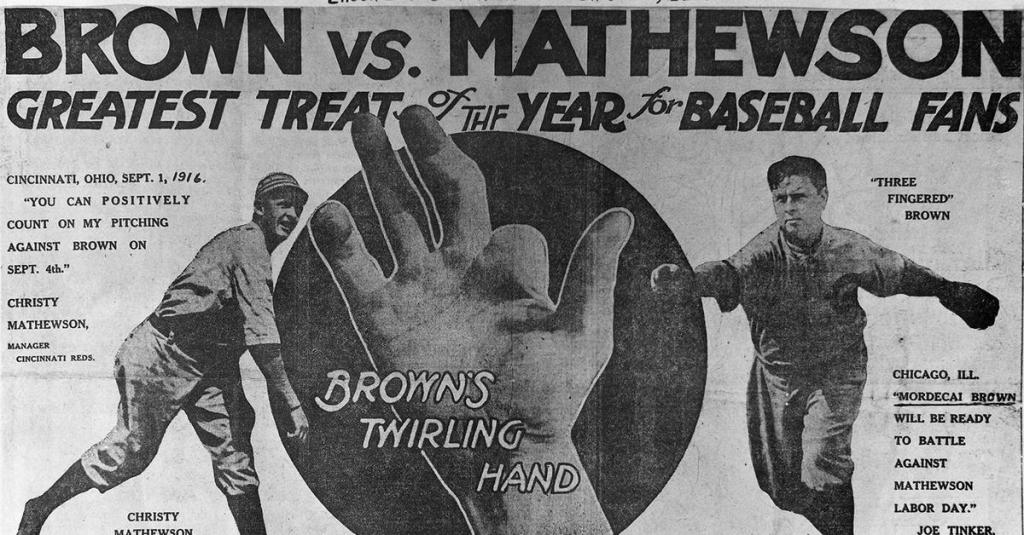

While Mathewson was viewed as a particularly good manager, he had little to work with in the last-place Reds, but he was permitted one notable moment as he played his only game outside of a Giants uniform on September 4, 1916.

“I’m through with pitching,” Mathewson told reporters; “I just want to work once more against Brown.”

Brown, of course, being Mordechai “Three Fingered” Brown of the Chicago Cubs, another Hall of Famer at the back-end of his own legendary career.

Matty was done on the bump, but he wanted one last dance with an old foe from their mutual peaks. The 36-year-old Mathewson yielded 15 hits in the game, but lost only narrowly to the 40-year-old Brown, 10-8 at Weeghman Park, known today of course as Wrigley Field.

Mathewson would manage the Reds through 1917, but during the 1918 season, he would be commissioned a captain in the Army’s Chemical Warfare Division and be deployed in France during World War I.

While overseas, Mathewson battled influenza and was exposed to Mustard gas during a training exercise. After his return, it was revealed that the Reds had hired a new manager after not receiving notice of Matty’s intent or capability of returning before spring training.

Mathewson resigned from the Reds and joined the Giants as assistant manager to John McGraw. In 1921, Mathewson, his side still ever painful and his years-long cough still plaguing him, was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Mathewson was given six weeks to live, but would endure for four more years, even getting a chance to run the Boston Braves as team president at the urging of his old skipper, McGraw, in 1923.

But in spite of his determination, Mathewson would succumb to his illness in October 1925 at the age of 45.

Matty received induction into the Hall of Fame in 1936 and was posthumously honored for that at the first-ever ceremony in 1939.

Amos Rusie, the man Mathewson replaced on the Giants as their star and leader, would tell reporters over 40 years after his career ended that he still felt twinges of pain in his right shoulder, and that if he hadn’t “gotten cute” with his pick-off move, which worked for the record, he would have lasted as long as Cy Young (22 years).

As is, Rusie played 10 years in professional baseball, and his career numbers – even by today’s standards – would fall short of Hall of Fame credentials at first glance.

246 wins, 1,950 strikeouts, 3.07 career ERA – all really good, but they don’t lurch out at you.

Look again.

In a league where strikeouts were scarce, Rusie dominated like no other. He led the league in strikeouts in five seasons, won over 30 games in four straight seasons, won over 20 games in eight consecutive seasons, and was worth 65.2 wins above replacement in his short, but powerful career.

Rusie’s closest career comparisons, according to Baseball Reference, are Hall of Famers Bob Feller, Bob Gibson, Jack Morris, Vic Willis, Jim Palmer, and Catfish Hunter.

In 1921, McGraw actually brought Rusie back to New York, where he served as a night watchman and later as superintendent of grounds at the Polo Grounds.

Rusie died in December 1942 at the age of 71, but would receive enshrinement at Cooperstown in 1977 via the Veteran’s Committee.

For both men, their stories are independent of one another, save for their cross purposes on December 15, 1900, when two owners, hell-bent on retribution and power consolidation, were still in the embryonic stages of their grand plan.

They may have known that Rusie was done, but neither man cared. Nor did they pay much mind to the “Christian Gentleman”, another of Mathewson’s colorful names, owing simply to his affordability and the ease in which two clubs working in concert could rip off his rights-holding club for every penny they had hoped to bring in for him.

In 1901, that trade was a footnote to the Grand Conspiracy. Today, it’s the headline, not the failed coup, and further reason to appreciate not just the noteworthy Hall of Famer we often hear about, but the other legend in this thing, the man who is responsible for where the pitchers mound is today, and why velocity became king.

The trade seemed to turn Rusie’s career off like a spigot and and turn Mathewson’s on all the same – that’s the intrigue, the so-called rip-off part of this deal.

But the only ripoff here is that Twitter didn’t exist in 1900.

Leave a comment